Video

games - a childish and sometimes dangerous pursuit, not worthy of being

spoken of in the same breath as music or movies, either in cultural or

economic terms?

Until recently, that was quite a common view in

Britain, not just in certain newspapers but among many politicians. But a

visit to Brighton this week should have been enough to convince anyone

that games have serious value.In the Metropole Hotel, often home to feverish politicking during party conferences, a less formally attired crowd has gathered for Britain's largest games conference. Develop, as the name suggests, is mainly for games developers, and they come to Brighton to listen (or doze through) presentations, to meet technology suppliers but above all to network.

This show is not so much for the US-owned publishing giants but for the myriad of tiny firms which make up Britain's thriving, if precarious, games development scene - and they desperately need to make contacts.

Typical was a two-man firm called Strangely Named, showing off "Bears Can't Drift?", a simple, attractive, racing game which they are building while holding down full-time jobs as university lecturers in games design.

But in the crowd of designers, students, entrepreneurs and technology vendors, there are also some research scientists. Their fields are genetics, public health and medical history and they have been invited here by the Wellcome Trust, the global public health charitable foundation.

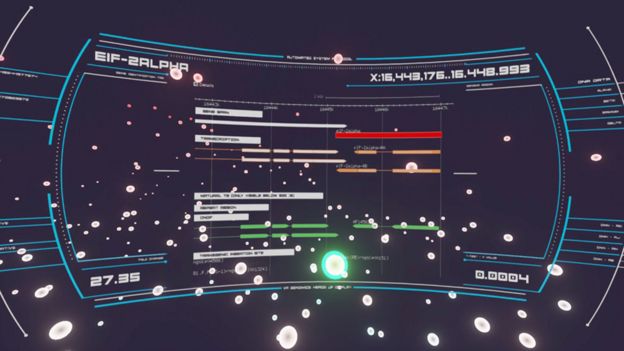

Why? Well they have come to see the results of a project which seeks to prove that games industry skills can solve a problem which is puzzling scientists in many fields - how to handle big data. The Wellcome Trust, which somewhat to my surprise has been working with the games industry for some years, has decided that virtual reality might offer an answer.

So it has teamed up with Epic Games to launch the VR Big Data challenge, a contest where developers have to come up with innovative ways to visualise huge datasets. The finalists are gathered in the Metropole Hotel, showing off their projects to the research scientists who might use them.

The game developers can choose from three datasets - the University of Bristol's ALSPAC study of children born in the early 1990s, the Sanger Institute's genome browser, and the historical Casebooks Project which examines 80,000 medical records from the 16th and 17th Centuries.

The contest is won by another firm tackling the child dataset, LumaPie. I ask one of the team, Pascal Auberson, why putting on a VR headset might be more useful to a researcher than simply examining a spreadsheet or looking at a conventional computer screen. "You can see depth and shape much more clearly," he explains. "It taps into the brain's natural ability to spot patterns."

But surely we should be writing computer programs to spot those patterns? "The human brain does some things better - you could write an algorithm to do it but you might as well just use your head."

What is really impressive is the range of skills that are present in games companies big and small - from designers to advanced software engineers - being employed in new ways. "We're taking the skills of game developers and applying them to the challenges of the science community, with which they've not had much interaction," Ian Dodgeon from the Wellcome Trust explains.

"As an industry we're used to handling big sets of data," Mike Gamble from Epic Games tells me. "Game worlds are built from millions and billions of polygons - human interactions, network interactions are very complex."

So the competition is an eye-opener for anyone who did not realise that building anything from Grand Theft Auto to Candy Crush Saga involves some extraordinarily smart and inventive people. Luckily, Britain is a global power in this field, a fact celebrated by the Culture Minister Ed Vaizey in a speech to the Develop conference.

I put it to him that much of the UK games industry is US-owned and that it's time for the financial community to start backing the sector. "This is the big story in tech," he admits. "The difference between the US and the UK is not about skills, it's about capital. We've got some ways to go in terms of getting that sophisticated investment community in the UK."

The games industry's scientific and cultural value are now being recognised. But an industry which supports thousands of jobs in clusters spread right across the UK, from Guildford to Dundee, still needs to persuade the City to come and play.

Post a Comment